In 2013, the first version of this paper was published in Advancing Philanthropy. With the 2015 US Supreme Court ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges securing marriage equality, and the increased number of American adults identifying as LGBTQ, the authors continue to believe the potential impact of giving by the LGBTQ community merits serious attention and strategy by nonprofit development experts. The focus of this paper is the potential impact to the nonprofit sector of planned gifts by the LGBTQ community.

According to a Gallup News 2017 report(1) approximately 4.1% of American adults now identify themselves as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender—which corresponds to an estimated 10 million adults as of January 2018. Further, according to Gallup, about 10% of the LGBT population is now married. If the median estate is multiplied by the number of persons identifying as LGBTQ or even by the number of married households, the potential for planned gifts is enormous—well in excess of $240 billion.

While strategies to attract participation and annual gift support from LGBTQ people are important, this article focuses primarily on larger gifts—both current and deferred—usually accomplished through charitable gift planning. Organizations that directly serve the LGBTQ population have the potential to attract significant gifts from this population; however, health-related organizations, arts and cultural institutions, and other organizations should consider giving focused attention to LGBTQ people.

Definitions: Estate Planning and Charitable Gift Planning

Estate planning is the process of accomplishing personal and financial goals while protecting individuals, their property, and those they love from personal and financial hardship. Estate planning includes planning for life’s challenges, including some or all of the following:

- managing property during life and after death;

- providing financial stability for oneself and one’s loved ones;

- protecting the mutual interests of couples in long-term relationships;

- preserving confidentiality;

- medical emergencies;

- temporary or long-term lifetime disability;

- minimizing taxes during life and at death; and

- leaving a legacy to support community causes and nonprofit organizations.

Charitable gift planning is the process of choosing the most appropriate gift for the most important purpose in the most advantageous timeframe for the donor, the charity, and the donor’s heirs.(2) Planned gifts, both current and deferred, are often given from accumulated assets, rather than current earnings. Many people have multiple charitable interests and want to make specific financial gifts to several different organizations.

Leaders of nonprofit organizations have a window of opportunity to identify and cultivate participants and supporters in the LGBTQ community and focus their engagement and fundraising activities toward the specific interests of this constituency. In the same way organizations may provide different services and cultivation tactics for ethnic groups, women, business leaders, or retirees, they should consider customized appeals to LGBTQ people.

As with the any segment of the population, LGBTQ persons require thoughtful estate planning, with attention focused on their special needs and considerations. (See insert below: Estate Planning and Charitable Gift Planning.) The next few years remain an especially important time to make the case for charitable gifts in estate plans with this constituency.

Why Reach Out to the LGBTQ Community?

- The Silent Generation (born between 1925 and 1944) and Baby Boomers (born between 1945 and 1964) may be the last cohorts of gay and lesbian singles and couples to be largely childless. With marriage equality in the US, reproductive techniques and adoption choice more plentiful, and same-sex couples enjoying acceptance by the broader community, younger generations of LGBTQ people are more likely to have children.

- These are the two generations born before the Stonewall riots (1969). They are passionate about equality and civil rights; they understand the huge gains and delicate fragility of the LGBTQ movement.

- Resources that have gone and currently go to 501(c)(4) lobbying and advocacy organizations (such as state equality organizations) may shift to 501(c)(3) organizations (such as education, health care, and anti-bullying programs) in the future. Some people may perceive a lessening of the critical need for advocacy and be more likely to broaden their charitable interests to specific services and quality of life issues.

Strategies to Attract LGBTQ Donors

- Make it known that your organization’s values align with the interests of the LGBTQ population. The Horizons Foundation study found that for the “overwhelming majority of LGBTQ donors, organizational effectiveness and efficiency rank high in their giving decisions.” To complement a data-driven case for support, organizations should illustrate their impact by including anecdotes about gays and lesbians as donors, volunteers, audience members, and service recipients.

- Expand gift planning beyond wills. When organizations decide to include gift planning in their development efforts, the development office often begins with a simple bequest program—asking current supporters to consider charitable gifts in their wills to the organization. One study, however, found nearly 60 percent of those who indicate that they have made a planned charitable bequest, in fact make no charitable transfers at their deaths.(3)

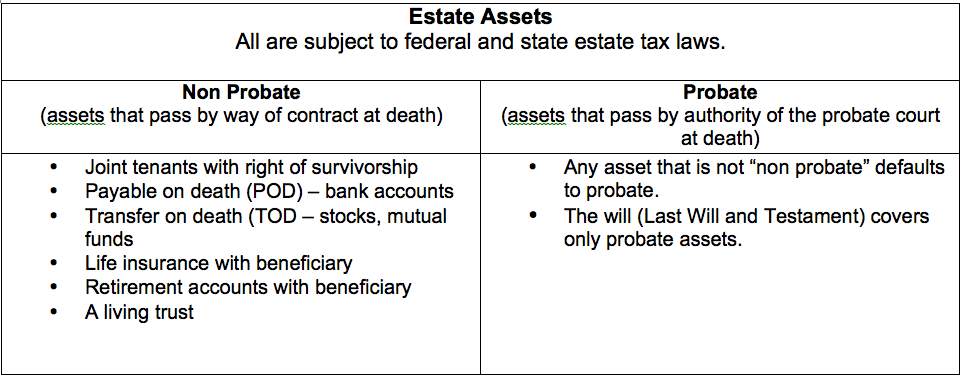

- We advise our nonprofit clients to discuss the use of non-probate assets (see Estate Assets chart below) with their prospective planned giving donors. These are excellent and generally simple choices for charitable gifts. While many LGBTQ donors will name their partner/spouse as primary beneficiary, charitable organizations are often the secondary beneficiary. The charities can be named the beneficiary of all or a portion of the asset. The donor can: 1. assure that a certain amount or percent will be received by the organization; 2. give the charity guidance as to the use of the gift by written instruction; and, 3. achieve confidentiality (non-probate assets are not public record). Or, the donor can name the organization as a contingent beneficiary.

- Introduce professional advisors to your organization and the programs and services it provides, including those specifically designed for the LGBTQ community. In larger communities, there are likely attorneys, accountants, and financial advisors who specialize in LGBTQ issues. Seek them out. The goal of these conversations is for the advisor to become knowledgeable about the organization, comfortable with its values, and aware of the impact of its services on its constituents and the community. The organization also wants the staff and board leadership to develop a relationship with the advisors and learn about their areas of expertise. Do not expect the advisor to recommend the organization to his or her clients; rather, when the client mentions the organization, expect the advisor to be familiar with and positive about the organization and ready to help the client achieve his/her charitable intentions.

- Help your clients leave a legacy for the next generation—and generations to follow. Some childless people effectively “adopt” favorite organizations—participating frequently in programs and services, volunteering in many capacities, and supporting fundraising campaigns and special events. Develop ways to recognize donors and commemorate major gifts. Start or augment a recognition group established for donors who have made plans to leave gifts to the organization through their estates.

Smaller organizations and those with less gift-planning experience may want to contact an affiliated organization or a local community foundation for technical support, investment expertise, or to establish organizational funds within the umbrella entity. Such affiliation can provide additional credibility for the organization and confidence for the prospective donor.

Case Study: Mary Zeiser and the LA Gay and Lesbian Center

Mary Zeiser isn’t your typical 24-year-old. While most people her age are busy dating, hanging out with family and friends, or building a career, the spunky L.A. native is focused on giving back to her community. At age 17, she signed up for AIDS/LifeCycle—the Center’s 7-day, 545-mile bike ride from San Francisco to Los Angeles that raises money for the Center’s HIV/AIDS-related services. She has since become active as a volunteer and fundraiser for several youth conferences and anti-bullying initiatives in LA schools.

After hearing Nellie Sims, then the Center’s Director of Planned Giving, speak at an event, Mary decided to take her giving a step further and made the Center the beneficiary of her life insurance policy, retirement plan, stock, and even her car. “There are no kids in my immediate family,” Mary said. “I consider the LGBTQ community and its youth to be my family. They need support from their elders. And while I may only be 24, I’m still an elder to some and I intend to do my part.” Mary illustrates how easy it is to do this—and do it now.

Conclusion

People who identify as LGBTQ are in every community – we live, work, worship, and play in cities and towns across America. Organizations that serve this population should attract and engage them in their work, seek their support, honor them for their commitment, and offer them opportunities to leave a legacy for the next generation. The window of opportunity is now.

For more information about particular estate planning issues for the LGBT community, see: http://www.horizonsfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/GuideToGiftPlanningForTheLGBTCommunity.pdf

- Gallup News: In US, More Adults Identifying as LGBT – 2017

- Newman, Diana S., Nonprofit Essentials: Endowment Building, Wiley & Sons, 2005.

- James, Russell N. III, “Barriers to Bequest Giving,” Advancing Philanthropy, May/June 2010.

This post written by Diana Newman, CFRE and Ron Guisinger, SPHR, CCP.